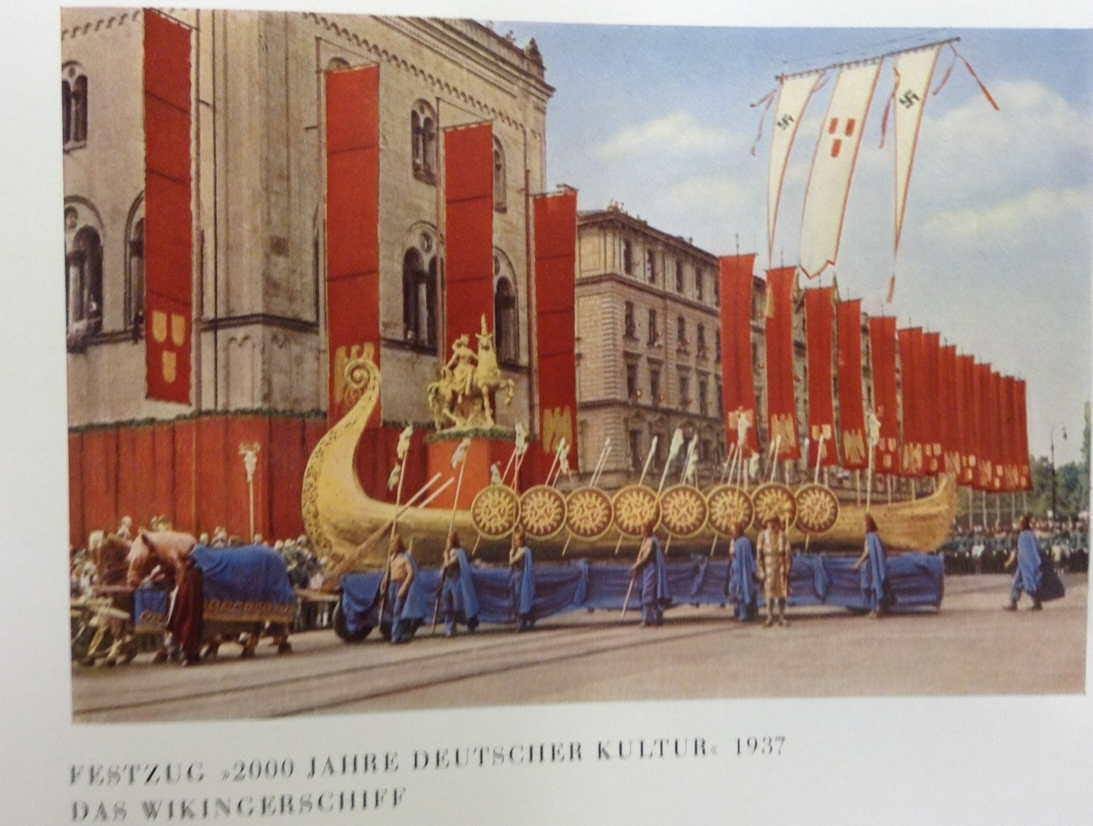

In 1933, the Nazi Party held a parade in Nuremberg, Germany, propagating an image of ethnic purity, racial heritage and importantly, a claim to what geographer and historian Joshua Hagen relates as: “‘Nordic-Germanic’ tribes as the earliest ancestors of modern Germans.”

During this portion of the 1933 parade, the “Nordic-Germanic” tribes were both “tall, weathered blondes” and accompanied a “Viking-like ship.” This imagery, as co-opted by the Nazi Party, centers whiteness and uses an imagined medieval past to justify Nazi policy and the genocide of the Jewish people. Adolf Hitler, in a 1927 speech in Nuremberg, outlines that “blood” is a crucial part of the Nazi state and claims that its purity must be protected for “national strength and power.”

This imagined medieval past is ultimately a false fantasy that justified hate. Professor of English Lindsey Row-Heyveld breaks it down as the difference between medieval history and medievalism, “the post-medieval fantasy of the medieval world.”

“By fantasy, I don’t mean necessarily only [in] literary [works],” Row-Heyveld said. “It’s the use of medieval aesthetics, art, narrative, lyric or architecture in a period that is not medieval. But it’s not the same as a thing from [the medieval] time period, or actual history from that time period.”

On November 23, 1927, several months after Hitler’s speech in Nuremberg and after a poll in this very newspaper, Luther College became the Norsemen. This symbol was chosen by the CHIPS staff and Luther students as a rallying point that could attest to the then-student bodies’ ethnic heritage of Norwegian immigrants, as well as a wish to harness the “bravery” of this image.

Luther Athletics used various “Viking” symbols, including the Viking longship for Women’s Track in 1986, and CHIPS has published several cartoons featuring a Norse. By 2002, Luther College formally adopted the image of the Norse helmet and horns and applied it en masse.

How can these images of Norse and Vikings, adopted or utilized during the same time period, be separated from each other? How can the medievalism of the Norse image be taken in two drastically different directions?

“Norse” has a multiplicity of meanings. The image of a helmet with horns, of hypermasculine raiders from the North is larger than life in pop culture, on the Luther football field, and even the “Pie King” outside Family Table in Decorah. The Viking is, at least around the Decorah area, woven into the social landscape. That image is ultimately ahistorical (meaning that it lacks historical perspective or context). Ahistorical, but not necessarily hateful either. Associate Professor of History Anna Peterson, who co-taught a class this fall semester called Vikings: Past and Present, asserts that the word “Norse” can mean different things in different contexts.

“One, it means someone from Norway, and second, it means somebody from the Scandinavian medieval period,” Peterson said. “So, it can mean a Viking, or it can just mean a Norwegian. I think what’s happened here is that those two things have been used interchangeably, or signaled, or at least that was the intent early on.”

Those multiple meanings are in tension with each other, and groups fashion these fictions that initiate both the Norse head as Luther students know it, as well as the medievalism of the Nazi Party. Peterson further spoke on how the undertones of the words “Norse” and “Viking” carry problematic meanings related to whiteness, white supremacy, and violence.

“I think it’s not just members of the far-right that have promoted those understandings,” Peterson said. “Those are the understandings that, going back to the 19th century when they ‘rediscover’ the Vikings, that’s what the Victorians were promoting. They’re also highlighting whiteness and racial supremacy in a way that makes it very difficult to separate the word [and] image of the Viking from those meanings.”

The deconstruction of this term from a history of white supremacy and racism is a difficult one, where the “problematic meanings” become blurred together with the more neutral images of Norse. Dialogue within schools currently using Norse and Viking logos has become exceedingly relevant, as modern-day white supremacists continue to use the “problematic meanings” of Viking and Norse. In fact, Luther students are told by administration and faculty leaders not to wear Luther apparel that features the “Norse” logo on J-term study abroad trips. History major Lydia Gruenwald (‘25), who was previously part of a Luther study away program in Vienna last January and Peterson’s Vikings: Past and Present class, was told not to wear the clothing with the Luther “Norse” logo in foreign countries by her professor.

“It’s common knowledge everywhere else in the world that this symbol, the Viking helmet, particularly with the horns, is a symbol for white supremacy,” Gruenwald said. “If we wore that on a study abroad trip, it would be like [saying that] Luther College is a white supremacist hate group.”

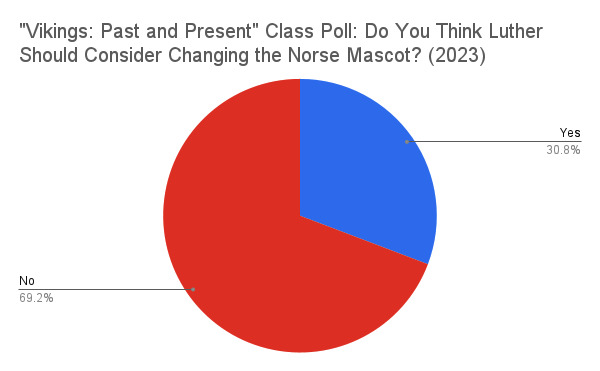

Despite the modern far rights’ use of Norse and its imagined past, many of the students in the Vikings: Past and Present class called for dialogue, not for out-and-out changing of the logo and mascot. Peterson shared a Google Form where those students voted and commented on whether the college should change the logo. Nine of the 12 students voted no, with one student giving the answer that “it is the least of Luther’s worries.”

Other collegiate students have chosen to demand change. The Associated Students of Western Washington University are demanding that the University change the mascot from the Vikings, claiming that the Viking narrative no longer fits with their mission statement of equity and inclusion. Their resolution states in part that “A strong majority of the task force recommends removal of the name “Viking” from the Viking Union,” a central building on Western Washington’s campus. As schools confront their Viking logo’s history, Gruenwald suggests that fostering dialogue is essential, even if removal isn’t the end goal or result.

“It’s important for students to know that the narrative the school promotes has been acknowledged to be a fictional narrative, and it’s not historically accurate,” Gruenwald said. “Which is ok, not everything has to be historically accurate. But our perception of this narrative has to be acknowledged, that [Norse] is a realized, fictional vision and not real. Being historically formed is very important, especially when it comes to white supremacy.”

Schools with the Norse or Viking image may face the consequences of white supremacist attachment to those logos and histories. An archived CHIPS article recounted that in 2018, Luther College found the image of a swastika and the letters “KKK” stomped into the snow of the football field.

Nonetheless, schools like Luther are also in a unique position to resist the narratives of white supremacy. While abandoning the logo can “fix” the problem, it also cedes the image to white supremacy altogether, without the possibility of reinterpreting what Norse can mean for the community. Row-Heyveld made it clear why the stories the community of Luther shares can have an impact on current-day white supremacy.

“What are we basing our shared community on, is it a shared sense of ethnic identity?” Row-Heyveld said. “We know that that’s increasingly not true at Luther College. If we are using ‘Norse’ not to mean a shared ethnic identity, but we are using the narrative, what do we mean by Norse? If it’s not actual ethnicity, it’s a different kind of shared identity that comes through community.”

Row-Heyveld suggests that focusing on the true stories of the Norse instead of on the “pretend stories about these people” that are being told by white supremacists, can reshape how we think of “Norse.”

“What are the [real] medieval Norse stories that we could tell that could represent us, that would refute the purposes of white supremacists who are trying to co-opt it?” Row-Heyveld said. “We need to make [Norse] a thing they don’t want.”